Water has an inherent draw to it, as a background feature on the landscape, as an acoustic presence, and as a loose part in play. But what about water as a vessel for giving children agency to define and guide their own scientific learning?

Biological sampling emerged as a natural extension of other kinds of water play in our field. The creek meanders alongside our playspace and following the spring melt the water becomes a popular ingredient in apothecary potions, mud kitchen dishes and art projects.

It was a bucketful of creek water intended for one of these uses last spring that yielded The First Fish.

After the initial exclamations and excitement settled, so too did some of the sediment in the bucket, and the children suddenly realized there was more than just a fish swimming around…in fact, there were all sizes, colours and shapes of creatures moving through the water column at various speeds, fluttering along the surface, or writhing their way along the bottom.

It was incredible to behold…both the bucket’s biodiversity and the reaction of our students. Across various age groups, across various days, word spread that there was life below the creek’s surface, and the children were mobilized. This background information was enough to help them make a testable hypothesis as an extension of their curiosity: will each bucket of water contain something that is alive?

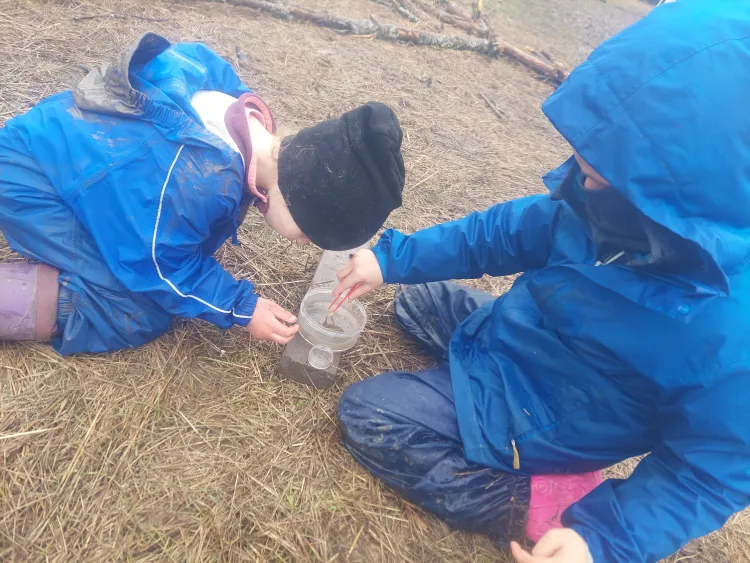

The methodologies varied across time, but the study always began with the collection of a sample of water from the creek’s edge. This area is dense with pillow-y tufts of tall grass that obscure the boundary between land and water. As such, and given the other attendant risks that come with facilitating play near water, this step of the process was either performed by an educator, or was closely attended by an educator.

After bringing the bucket back onto solid land, there was usually a rush to peer into the sample’s murky depths, squinting for a hint of movement in opposition to the visible currents. Occasionally something large would make a dramatic appearance at this stage, but generally the bucket would need to be hoisted into the air and the sample decanted into subsequent containers meant to clarify the water and reveal its inhabitants. I was continually surprised by how slowly and methodically the children searched these samples for life. While some students filtered in and out of the process based on the exciting-ness of the latest discovery, others sunk in deep and stayed there throughout the entirety of our time at site. They figured out that a white bottomed bin produced the best visibility, and so they requested more of the same. They asked to use their own drinking water to dilute cloudy water, and we happily pointed them to the rain barrel instead. This was a revolution in the clarifying process. Eventually someone brought a plastic aquarium from home, and our processing and observation set-up peaked.

There was ongoing discussion between students throughout the sampling process, and it could become heated. Sometimes we educators would step in to frame the conversation more productively, to help them through differences in opinion about what they were observing, or how something should/could be done. Furthermore, there was a scarcity of space around the tables, and only so many heads could fit over a bucket at one time. And for some, there was a study design that needed to be adhered to. Eventually, with some gentle guidance, we reached an understanding that creek sampling was an activity that could include students in a diverse variety of tasks suited to their interests and inclinations. Overall, it was a great opportunity for all of us to practice communicating in ways that are kind and accessible to people of different ages and scientific backgrounds, even we’re communicating about something we feel passionately about.

Of course, through all of this “stand back and let the inquiry happen!” mentality, the educator has a very specific and pressing role to play in the water sampling process: overseer of animal ethics. There is an obvious tension between capturing and observing animals, and our usual forest school tenets of consent and respectful co-existence when interacting with our animal friends. However, we are absolutely able to do water sampling in a way that feels in line with our philosophies, that balance the value of experiential learning with the need to discuss and challenge the ways that doing science hasn’t always been “right.” And by having these conversations all the time, water sampling has proven to be an amazing opportunity to engage our students in active empathy and compassion as well as scientific thinking.

What does this philosophical balance look like in practice? Our samples are taken randomly from the shoreline, and are returned to the same place once they have been examined. And in between catch and release, we are calm and gentle with the water and with the creatures in it. An easy benchmark that I learned somewhere along the way: we only catch an animal once. It’s simple and unequivocal and it can be front-loaded and returned to as necessary. We don’t count taking the initial sample as a “catch,” but once that bucket of water has been decanted into another container for the purposes of finding creatures within, everything in that container can only be caught once. For example, if we are partitioning beetles into a separate container for analysis and observation, each beetle can be gently caught with a spoon or similar implement and moved into the beetle tank. Then it gets to swim freely until it is returned to the creek. Similarly if a fish is found in a sample, it can be gently scooped up once to be moved into a clear sided container for better viewing and identification. Then it gets plants/landscaping added to make it feel more comfortable during its time on land, but no further tools go into its space.

A water bug with eggs on its back.

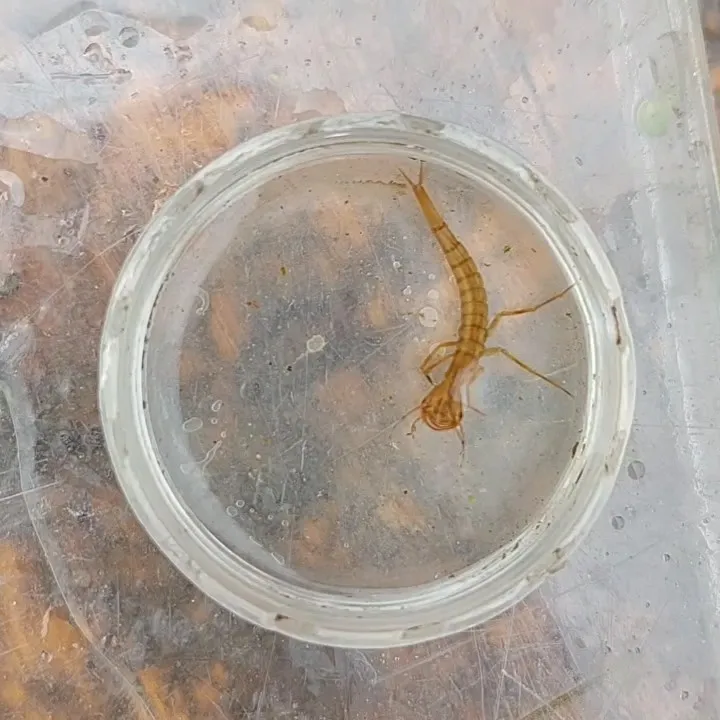

A predaceous diving beetle larvae, as identified by our students

We discuss whether or not it feels okay to put our hands in the water—what we might have touched, how reliant these creatures and their tiny bodies are on clean water. One older group instituted a multi-step hand washing process for anyone who wanted to interact with any stage of the samples. First, the individual was asked to wash their hands at the bathroom hand-washing station (hand soap, potable water, foot pump). Then, they were provided with a bin of (regularly changed) rain barrel water in which to rinse any final soap residue from their skin before touching the instruments that would come into contact with the water.

Sometimes, the vibe of a group isn’t right for interacting physically with our sample, but the interest is absolutely there. Maybe in those moments, the sample can be poured once from the bucket into an “observation tank,” and we can sit in a small circle with our students to gaze and exclaim over the creatures within without touching them.

We provided the same sampling loose parts to the Fox groups (4-8 year olds) and the children were similarly captivated by the life in the pond adjacent to their playspace. It was genuinely astonishing to see how sustained their individual and group interest was in discovering what tiny life fluttered within their buckets of water. They would spend amazing lengths of time staring into a single sample, and would joyfully bring others in to share in what they were witnessing. There were never any fish or tadpoles in the pond, but there were snails, zooplankton, amphipods, and other forms of mysterious movement in water they had scooped themselves, and this was more than enough to thrill and captivate the children. Week after week they would return to their materials and their methodologies, and when it was time to leave for a hike, they would ask to leave their setup intact so the investigation could recommence immediately upon our return.

Whatever the inquiry looks like, when it has reached a logical end for the moment, we ceremoniously return all the water and its inhabitants to the same part of the shoreline from which it came. We say “Thank you for the visit,” as is our habit when we’ve interacted with an animal on the land, and we watch the water and all its tiny stories pour back into the greater pool of currents and life and curiosity.

As part of a larger framework for creating lifelong learners and scientific thinkers, we as educators can invite children to notice that there is wonder to be found everywhere. We can reinforce their curiosity, and when we provide them with the means to follow their own inquiry to a natural end, we can assume an immense level of competency in their ability to do “real science.” The spring melt has brought water sampling back into our daily rhythms, and the older students have begun making requests for more detailed field guides than we have on hand. We hope to procure more “laboratory equipment” from the thrift store, and we’re wondering about our students’ interest in creating some kind of record of what we find. None of us are sure where the continuing inquiry will take us, but we are all curious to find out!